Our Patients:

Brystol Carter

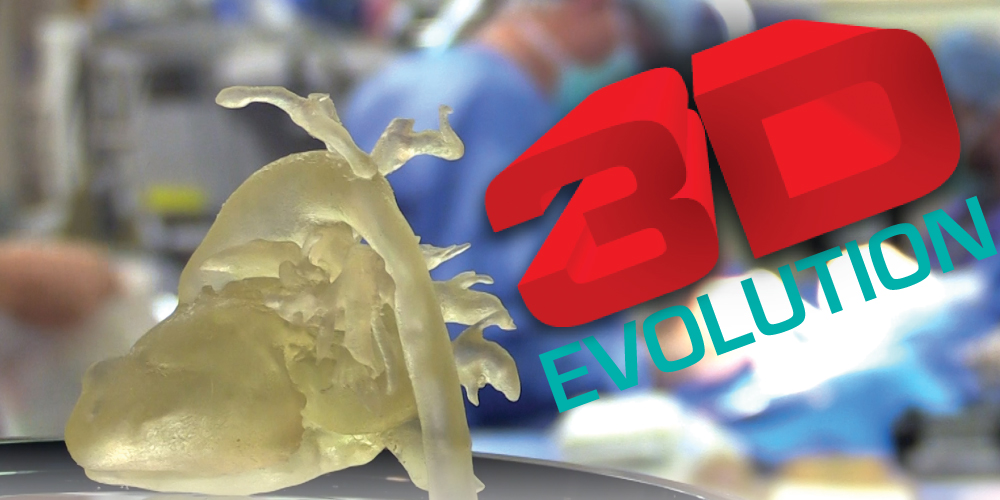

“It was eye-opening; this was really what her heart looked like,” she said as she recalled holding the model in the palm of her hand at SSM Health Cardinal Glennon Children’s Hospital. “I was in awe that it was even possible to make something like this to see where everything was positioned.” Brystol Carter was born in September, 2014 with a series of medical conditions, including two holes in her heart and a missing segment in the heart’s main circulatory pathway called the aortic arch.

As a newborn, her heart was so small, surgeons wanted to be sure to “map” out the best way to make the complicated repairs. Instead of reviewing multiple two-dimensional CT scans, however, this time, they were able to touch, rotate and look at an exact plastic replica of Brystol’s heart, made by a 3-D printer in an engineering lab at Saint Louis University.

“We’ve been doing 3-D modeling for heart patients at SSM Health Cardinal Glennon for more than a year now,” says cardiologist Wilson King, MD, one of the medical center’s first advocates of 3-D modeling for complex pediatric heart surgery. “Brystol’s heart when she was just 18 days old was among the first we did and it dramatically showed the benefits of this technology for both education and presurgical planning.”

The use of 3-D models is gaining momentum in medicine. At SSM Health Cardinal Glennon, they are used for some complex cases in:

- Cardiology

- Plastic Surgery-Craniofacial surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Orthopedics

“It’s an evolution from what we’ve been able to offer in imaging,” says radiologist Nadeem Parkar, MD, Chief of Cardiac and Thoracic imaging. “For years, we would look at the heart and other structures in two dimensions. Then, several years ago, we started using computer software that used multiple two-dimensional images to create a virtual 3-D image on the computer screen that we could rotate and examine. Now, with the rapid technological advancement, we can create a 3-D printed model using the two dimensional images from CT or MIRI and post-processing those images using advanced software and a 3-D printer.”

In theory, 3-D printers work much like a standard office printer, printing copies of whatever is sent to the printer. The difference is that instead of ink, 3-D printers print substances, such as plastic or metal. Over the course of 12-24 hours, 3-D printers move back and forth, building layer upon layer, until an accurate model is created.

3-D modeling is expensive due to the time involved for multiple imaging scans and software manipulation, as well as for the cost of equipment and materials. To prove the medical benefits related to 3-D printing, Dr. King paid for the first few models out of pocket. “When we started showing the models to other people, they came and asked if we could do it for their specialty,” he says. “Currently the demand is so overwhelming, we don’t have enough time, manpower and equipment. We need our own fully staffed and equipped 3-D center at Cardinal Glennon.”

Alexander Lin, M.D., is Chief of Pediatric Plastic Surgery and Director of the St. Louis Cleft-Cranofacial Center at SSM Health Cardinal Glennon. He is nationally recognized for his expertise in treating complex craniofacial anomalies as well as congenital deformities in infants and children. He has dozens of colorful 3-D models in his office that the Plastic Surgery Department has used for pre-surgical planning over the past several years.

“Access to the technology is limited and it’s expensive,” he admits. “Because of that, we use 3-D modeling only for exceptional cases, such as for children with very unusual anomalies that were located close to the brain or other vital structures.”

By also having his models printed in surgical-grade materials instead of plain plastic, Lin has the added benefit of being able to take his models directly into surgery.

“By having the sterilized model next to me in the operating room, I can make continual measurements on it to ensure greater accuracy during the actual surgery,” Dr. Lin says.

Especially with facial surgery, Dr. Lin is adept at minimizing incisions to avoid long-term scarring in children. By having his 3-D models printed commercially, he can separate key components — jawbone, cheekbone, orbits, forehead, etc. — so that they can be manipulated to determine the best surgical approach.

Dr. Lin now is pursuing grants to fund the purchase of a 3-D camera system that would take highly accurate images of craniofacial patients. “A 3-D camera is a complex set of 12 cameras in a ring on the ceiling,” he explains. “In only a few milliseconds, the camera would take about one thousand photos from all angles, which we can then use to create better 3-D models.”

He wants to bundle that system with a 3-D cone beam scanner, which functions like a typical CT scanner, but at a lower dosage, and therefore safer for children. Add to that a large 3-D printer onsite that could be used by multiple pediatric specialists and print with surgical grade materials, and SSM Health Cardinal Glennon envisions a premier 3-D Center of Excellence. “With this center, I think we could innovate very rapidly,” Dr. Lin says.

All totaled, pediatric specialists here say that the cost to establish and then staff a 3-D Center of Excellence would run into the hundreds of thousands of dollars. “It is expensive, but it’s applicable to many, many fields of medicine,” says Dr. King.

It’s incredibly beneficial to educating the next generation of physicians, too. “It absolutely can revolutionize how we teach the next generation of surgeons because trainees will know the individual patient’s anatomy in three dimensions before going into surgery,” says Dr. Parkar. “Over a period of time, you can have a library of 3-D models of different pathologies for medical students and trainees to study.”

Amanda and Chad Carter don’t really know all about the far-reaching implications of 3-D printing in medicine. What they do know is that they came to the right place for Brystol’s medical care. The family lives in East Prairie, down in southeastern Missouri. After Amanda had an earlier miscarriage, six-year-old Brayden prayed for a sibling to join the family. “I became pregnant soon after and I thought, wow, Brayden’s prayers were answered,” says Carter.

Visits to her obstetrician in Cape Girardeau identified early medical concerns with the baby and Amanda was referred to the St. Louis Fetal Care Institute at SSM Health Cardinal Glennon. The family focused on one bible verse they picked for their unborn child: Every good gift and every perfect gift is from above, and cometh down from the Father of lights, with whom is no variableness, neither shadow of turning. James 1:17

“We have a lot of faith and I had a great sense of peace that this was where God placed us,” said Amanda. “I knew we had some serious things to overcome, but everyone at Cardinal Glennon was so compassionate and caring.”

Today, at almost 8 months old, Brystol’s heart is functioning well. In the coming year, she is expected to undergo surgeries by plastic surgeons to repair her cleft palate and foot anomalies, but Amanda says faith in God and SSM Health Cardinal Glennon keeps them going.

“We have an amazing church family that continues to lift us up in prayers and we have an amazing team of doctors that continues to take care of Brystol,” says Amanda. “This 3-D modeling is wonderful, but the real miracle is how God brought all of this together.”